Rising Food Insecurity in Washington: What's Behind It and What We Can Do

- Home

- Rising Food Insecurity in Washington: What’s Behind It and What We Can Do

By: Babs Roberts & Claire Lane

Food insecurity is more than hunger. It’s the economic and social condition of not having consistent access to enough food for a healthy life. When a household runs out of food before the end of the month and can’t afford more, that’s food insecurity.

Even though Washington ranks among the top 10 states with the lowest rate of food insecurity, the situation is far from ideal. In 2023, 9.5% of Washington households experienced food insecurity (1), and that number is on the rise.

What’s Causing the Increase?

The reasons behind this growth are complex, but two key factors stand out: rising food and housing costs and the end of COVID-era assistance programs. These economic pressures are pushing more families into difficult choices between groceries, rent, and other essentials.

The Fall 2024 Washington State Food Security Survey(2) highlights that groceries have now become the most difficult household expense to afford, even surpassing housing. While food insecurity affects people across all demographics, it doesn’t affect everyone equally.

Who’s Most Affected?

Certain groups continue to bear the brunt of food insecurity in Washington. Households with children, larger families, and those with lower incomes are hit hardest. Racial disparities are also stark: Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, and multiracial households experience food insecurity at disproportionately high rates.

What’s particularly concerning is that even middle-income families are increasingly vulnerable. About a third of households earning between $75,000 and $150,000 reported being food insecure. These families often earn too much to qualify for federal assistance but are still struggling to meet basic needs.

How Are Washingtonians Coping?

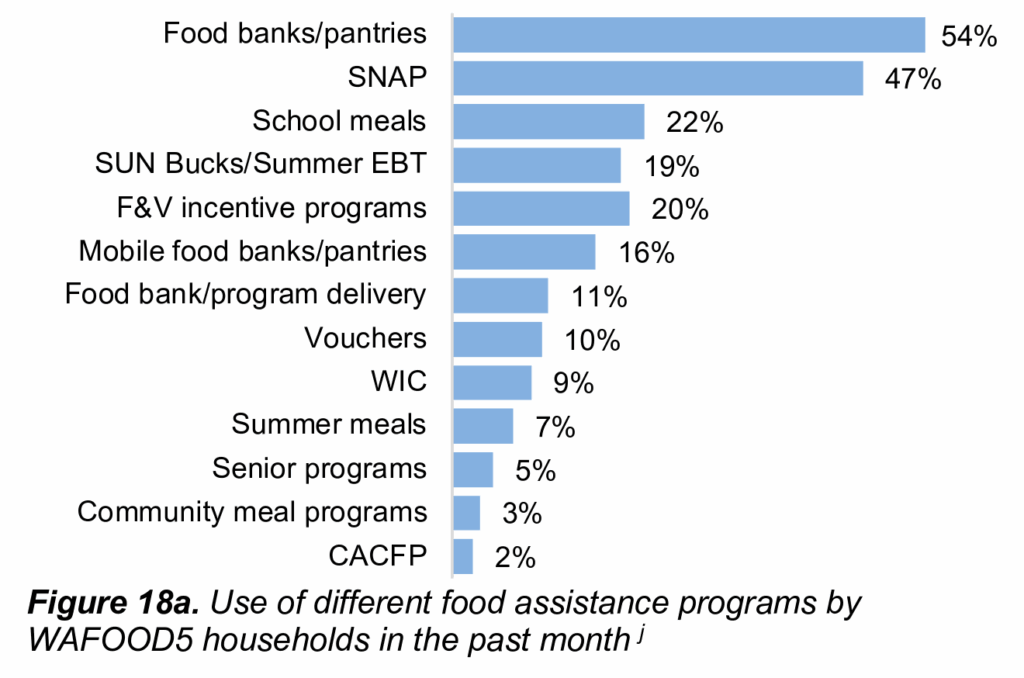

Many people turn to food assistance programs such as SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program), food banks, and school-based meal programs. Last year, more than 920,000 Washingtonians—roughly 11.5% of the population—used SNAP benefits. Of those, 35% were children and 32% were elderly or disabled adults.

Meanwhile, demand on food banks has soared. According to the Washington State Department of Agriculture, food banks across the state saw 13.4 million visits in 2024, compared to just 7.8 million in 2019 before the pandemic. Historically, SNAP has been the most commonly used food assistance program, but new data from WAFOOD shows that food banks are now the most commonly used, suggesting that more people with incomes too high to qualify for SNAP are needing to access food assistance to get by.

New Legislation Threatens Access to Food Assistance

Unfortunately, just as need is rising, federal support is shrinking. The newly passed One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) is reshaping the SNAP program with sweeping changes that reduce benefit levels, limit eligibility, and shift significant costs onto the states.

The bill increases work requirements for many, including veterans, homeless individuals, parents of teenagers, and adults over 55. It also cuts access for most immigrants who are lawful permanent residents but don’t yet have green cards. Those unable to prove consistent employment of at least 20 hours per week risk losing their benefits altogether.

In addition to reducing access, the bill transfers much of the financial responsibility of SNAP—from benefits to administrative costs—to the states, placing an enormous strain on already tight state budgets. These changes come alongside parallel cuts to Medicaid, creating a compounded burden for households that rely on both programs.

The Growing Strain on Washington’s Food System

The impact on emergency food systems will be immediate and intense. Food banks, pantries, and community meal programs—many already stretched thin—will be forced to absorb even greater demand. But these organizations cannot and should not be expected to carry the full weight of national policy changes.

A Path Forward: Coordination and Community Support

To address rising food insecurity, Washington must strengthen coordination across federal, state, and community efforts. There’s room to improve access and participation in several underutilized programs.

Take WIC (Women, Infants, and Children), for example. WIC provides healthy food, nutrition education, and healthcare referrals to families with young children, yet only about 53% of eligible families in Washington are enrolled, according to USDA estimatesiii. Improving the reach of this program could make a significant difference.

New programs like Summer EBT, launched in 2024 by DSHS and OSPI, have already proven effective—providing food benefits to over 590,000 children statewide. Continued investment in this and other child nutrition programs will be critical, especially during school breaks when hunger spikes.

Incentive programs like GusNIP, run by the Washington State Department of Health, also show promise. By helping SNAP families afford fruits and vegetables, GusNIP supports both nutrition and food access, especially for those working with limited resources.

Conclusion: We Must Act Together

As federal policies shift and costs continue to climb, Washington’s Economic Justice Alliance is committed to protecting access to important basic need supports to the extent possible and will continue to collaborate across our partnership to support the anti-hunger ecosystem in Washington State.

The path forward will require cooperation between lawmakers, community organizations, public health leaders, and every Washingtonian who cares about equity and access to food.

Citations

1. Rabbitt, M. P., Reed-Jones, M., Hales, L. J., & Burke, M. P. (2024). Household food security in the United States in 2023 (Report No. ERR-337). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. https://doi.org/10.32747/2024.8583175.ers

2. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2022). Policy Basics: The Child Tax Credit, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/policy-basics-the-child-tax-credit

3. Ananat, E., Glasner, B., Hamilton, C., Parolin, Z., & Pignatti, C. (2024). Effects of the expanded Child Tax Credit on employment outcomes. Journal of Public Economics, 238, 105168–105168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2024.105168

4. Otten, J. J., Spiker, M. L., Dai, J., Buszkiewicz, J. H., Beese, S., Collier, S. M., & Ismach, A. (2025, February 13). Food security and food assistance in the wake of COVID‑19: A 5th survey (2024) of Washington State households (Research Brief 16, WAFOOD5). Washington State Food Security Survey. University of Washington & Washington State University. https://foodsystems.uw.edu/cphn/wafood/brief-16